- 26 May 2021 21:34

#15174267

Indeed Airbnb takes a cut from guests and hosts as a commission for bookings, they provide the service of brokering, which is a bit differently than merely advertising as they're trying to directly connect you to the service rather than simply make an appeal to you to use the service. Hence why Airbnb actually pays for advertising and marketing as separate from its app platform as it does need promotion for people to come to the app.

But this is where I'm trying to drill in a distinction between a contract laborer as distinct from the petty bourgeoisie or small business owner. Contract labor isn't so essentially different from the wage laborer as to not be part of the working class.

Here's a good summary to emphasize what I already did in which wages are pushed down in part because of the competition among workers whose livelihood is precarious.

https://www.marxists.org/glossary/terms/c/o.htm

Now see the above how the direct ownership of the means of production doesn't stop a capitalist still profiting from the work of others. You seem to make no distinction in quality between the person who does all the work themselves in maintaining an airbnb directly in their own home with renting out a room in comparison to the person who has the capital to invest in alternative properties and even hire employees or other workers.

The small business owners in fact have the means to become independent of airbnb.

https://c94e25ea-37c0-4c5f-bd71-5f6fcac47514.Perhaps%20because%20risk%20in%20the%20workplace%20is%20no%20longer%20assumed%20solely%20by%20entrepreneurs%20(Hacker,%202006;%20Pugh,%202015),%20workers%20for%20these%20services%20do%20not%20generally%20view%20sharing%20economy%20work%20as%20entrepreneurial%20unless%20they%20have%20taken%20on%20considerable%20financial%20risks%20(such%20as%20renting%20multiple%20apartments)%20and%20hiring%20other%20workers.%20In%20some%20cases,%20such%20as%20with%20Kitchensurfing%20chefs,%20sharing%20economy%20work%20was%20viewed%20as%20part%20of%20a%20marketing%20effort%20for%20a%20separate%20company%20outside%20of%20the%20so-called%20sharing%20economy.%20filesusr.com/ugd/e5771f_112374073d3d403f92f5ebab52170590.pdf

This point of the relevative independence of those who use Airbnb to host multiple units and their ability to actually work independently of airbnb if they so chose, to me emphasizes a distinction between them an what may count as employees in the case of those who do all the work themselves. They provide their own personal home space, they do the cleaning and so on.

Consider this piece which argue that under California law currently, Airbnb hosts would be considered independent contractors, but with their proposed ABC test, they would fail to be considered as such.

https://poseidon01.ssrn.com/delivery.php?ID=004020091089127119019087003092003075120015077012021005105006110113075120101113096030041107053119007034112080088111123066030005053026022082043007070010115071077100090015042078014124113094026075120100102104003108121110093004070120013097119011082097017&EXT=pdf&INDEX=TRUE

I imagine you and others might emphasize part 1/A, that the lack of such direct control by Airbnb emphasizes how they're not workers but truly are independent. This is certainly a defensible advantage for Airbnb as compared to other platforms for the gig economy and I felt was a weak point in some earlier criticisms. However what does resonate are the other two points which follows from my above points about the relative independence of the individuals to work separately or outside airbnb or not. Those who are solely dependent on airbnb bringing the market to them are more likely to be considered employees while those who have carved out a niche for themselves outside or it or could readily do so and are even close to doing so such as the aspiring hotelier, are more distinctly small business owners.

The article itself seems to go even further to emphasize that those who I would perhaps see as closer to being small business owners are not as such if they remain entirely dependent on the airbnb platform, they are markedly not independent enough to be considered independent contractors but are employees essential to Airbnbs business model.

I didn't generalize all interests in starting a business as motivated by leisure but emphasized the interview aspiring to a point of profitability that it became a passive income.

Do you think passive income doesn't exist for those who have ownership and do not have to be so actively involved in their business as they delegrate to employees?

Also lost in your emphasis of merely taking financial risks is also the ability to even take such risks, that is to have such money in order to invest it as capital in the first place. Some people may qualify for loans but plenty don't because their situation doesn't allow great confidence in their ability to pay it back and so is too much risk for those who give out the loans.

The quote on the interviewees emphasizes how they have the skills and capital to pursue a business outside of airbnb. That can be the same aspiration for employees of course, as mentioned, that basically are workers in a extremely precarious situation and thus end up in contract work.

But thinking of the skilled contractor, they tend to be distinguished also in the fact that they sell private labor and as such do have relative independence due to the demand of their skills.

https://www.marxists.org/glossary/terms/c/o.htm#contract-labour

Here again I think you're trying to emphasize sameness in order to disrupt any distinction between a worker and petit-bourgeois. Instead of emphasizing the precariousness, it all gets subsumed under risk of investment. The idea here that workers are simply taking a risk for the prospect of more 'profit'.

Which again I think is muddying the waters a bit like how one might frame all of prostitution in terms of women who have the means to voluntarily leave the profession compared to those who are coerced into it out of poverty or what ever. As if they're the same person. So to the person who can't find stable employment and is pressed into the gig/sharing economy is equated with the same people who actually succeeded at airbnb in starting up the basis of a small business with airbnb as a starting point to tap into the market.

Airbnb hosts can't simply state there is a room available, they have to appeal to the taste and expectation of their customers to be competitive.

https://www.cnbc.com/2019/07/03/is-running-an-airbnb-profitable-heres-what-you-need-to-know.html

They basically need to be like a hotel in their services except the host pays for this all upfront, so they need the sort of cash to be able to supply all this. And see how the money saver comes in the form of putting in your own work.

Now the host takes on the risk, puts in the investment and does all the work, but focusing on the earlier quotes, while airbnb doesn't own anything, the person works for airbnb as they are not independent workers who happens o contract with airbnb but are entirely dependent on airbnbs brokering as is airbnb dependent on the host doing all the leg work. They effectively socially coordinate the work which is a prerequisite for them to actually make some money, which they cannot do without airbnb and if they can then they are more distinctly an independent contractor rather than an employee who has to to not only work but bring in the materials, land and so on necessary for the work. A bit like how workers aren't invested in being trained anymore but have to take that as a personal cost, more and more is shifted back onto workers so as to put risks and costs back on individuals and to not detract from profits and make all the more precarious workers as in an unregulated labor market.

Indeed, its a lucrative risk to take.

Here you would seem to be agreeable with the above points of how the hosts are not independent of airbnb's platform and may not necessarily have the means to be as such if the market for them ends with the lack of airbnb.

Indeed the broader problem being the contradiction between exchange value and use value, there is great need but effective demand is what matters in the economy.

https://critiqueofcrisistheory.wordpress.com/crisis-theories-underconsumption/

However, Airbnb is just par of exacerbating this issue in which human needs become increasingly detached from exchange value. YOu end up with people unable to find housing because there is more money in the short term. See an issue with CHinas use of real estate as investment properties for their wealth which leads to all sorts of unused homes because its about money, not use.

Indeed, New York and all major cities are ridiculous because of the high demand for the small space. I actually enjoy living in a small town where I can afford a decent sized home for a much lower price and works out well having an education and access to the few decent paying jobs here.

Indeed regulations have to be introduced for the changed market to try and balance out some of the effects within some tolerable range. Just like how many hosts are treated as independent contractors as opposed to employees.

Indeed women being primarily tasked with dependents results in them adopting more flexible jobs, and more flexible jobs such as these of course means higher risks, lower pay and so on.

Which is exactly why it benefits businesses to mark them as independent contractors as opposed to employees with what labor laws exist having applicability.

https://www.jacobinmag.com/2015/05/freelance-independent-contractor-union-precariat/

So basically it takes advantage of the structures in which women's responsibilities compel them to look for such flexibility.

The dynamic being that dependents aren't well supported within capitalism and those who receive the most support often are those of the higher wages/incomes.

https://www.ethicalpolitics.org/ablunden/pdfs/social.pdf

Even when one seeks childcare in the paid form its still low and if it isn't low it's simply not affordable for many and negates the point of even going to work.

Flexibility is always appealing but as you recognize it of course entails other costs rather than it being something built into the structure of society to support families.

It's not simply a preference for flexibility, one has to actually consider what are the structural relations which dictate one's opportunities? It is easy to frame workers as all purely voluntary and such and without any coercion under the way in which structural relations of class and so on are made absent in a lot of descriptions of economics.

Touching upon things but not really relating them within the social context all that much, things are just taken as a natural given because there is a kind of naturalization of capitalist production and relations. However it is contestable.

https://kapitalism101.wordpress.com/2011/09/30/marginal-futility-reflections-on-simon-clarkes-marx-marginalism-and-modern-sociology/

Basically, there is much to question in the way in which some presentations of decisions of people as many simply take what is at face value and do not critique it. A bit like how one might go well women earn less because they don't get the higher paying jobs, why? Because they choose to enter into more flexible lower paying kinds of work in order to care for dependents instead of pursue their careers. Why is that? Well their decisions are made within a social context and only make sense when related to the social whole because individual actions are nonsense confined to only the individual.

https://aifs.gov.au/publications/family-matters/issue-86/persistent-work-family-strain-among-australian-mothers

https://scholarcommons.scu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1048&context=phi

This is seen in the limitations of microeconomics when expanded to macroeconomics.

http://frankackerman.com/publications/economictheory/Interpreting_Failure_Equilibrium_Theory.pdf

This is in part why things like class are fundamental, because people aren't abstractly all the same individual making similar decisions. They are subject to different constrains and the constraint of someone who is working class is fundamentally different to that of other classes. As such, one can be critical of the way in which one might try to present workers as the same as other classes in a superficial way. Hiding the coercion of how they're compelled to work to meet their livelihood compared to that of a capitalist.

And people are often happy to trade off lower cost for less quality control.

Although it seems as pressure has mounted, Airbnb has become on par in cost with Hotels.

https://www.washingtonpost.com/travel/2021/05/25/airbnb-fees-cleaning-hotels/?outputType=amp

So it's losing that cost advantage perhaps.

I also would distinguish between the small business owner and capitalist in terms of risk as a lot of risk for capitalists does not destroy them financially as it does the small business owner who in the long run have a tendency to return to the proletarian class. When one thinks of the losses incurred on Airbnb, they cut those loses by cutting off workers and so on.

https://www.wired.com/story/airbnb-quietly-fired-hundreds-of-contract-workers-im-one-of-them/

Who is hurt more here, the company owners or the workers?

BUt of course there is a tendency to generalize the small business owner who invests what little excess wealth they have into risky ventures in the hopes of establishing something bigger for themselves like the guy who aspired for a passive income.

Again, a millionaire may take a gamble on something but how much it really hurts them personally as the company owner is distinct in its nature to that of the worker or small business owner.

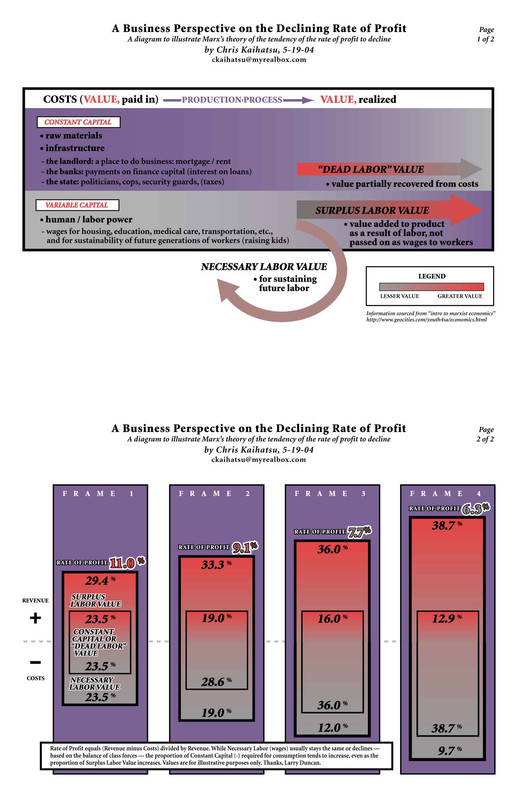

Well for example one is pretty much making untenable the idea of exploitation of labor and thus the very theory of value. If there are no classes, then the presentation of people as simply equal agents on the market abstracted of their structural relations makes equality of the market seem natural and self evident. Everyone is on par with one another. But as mentioned earlier in simon clarkes critique of marginalism, that the different resource ednowments must be structural if they're to be ongoing and one must look to property and production relations to actually find that labourers are a distinct class from capitalists when they come to the market for exchange of their labour power. And they are coerced into such work by the structural deprivation of any means of subsistence, they have to work to survive. Without such a structural relation, capitalism would not have a means of forcing productivity and intense measures upon the working class.

It's whether the difference marks an essential point of their real attraction to one another. Workers and capitalists are brought into a constant interaction due to structural lacking.

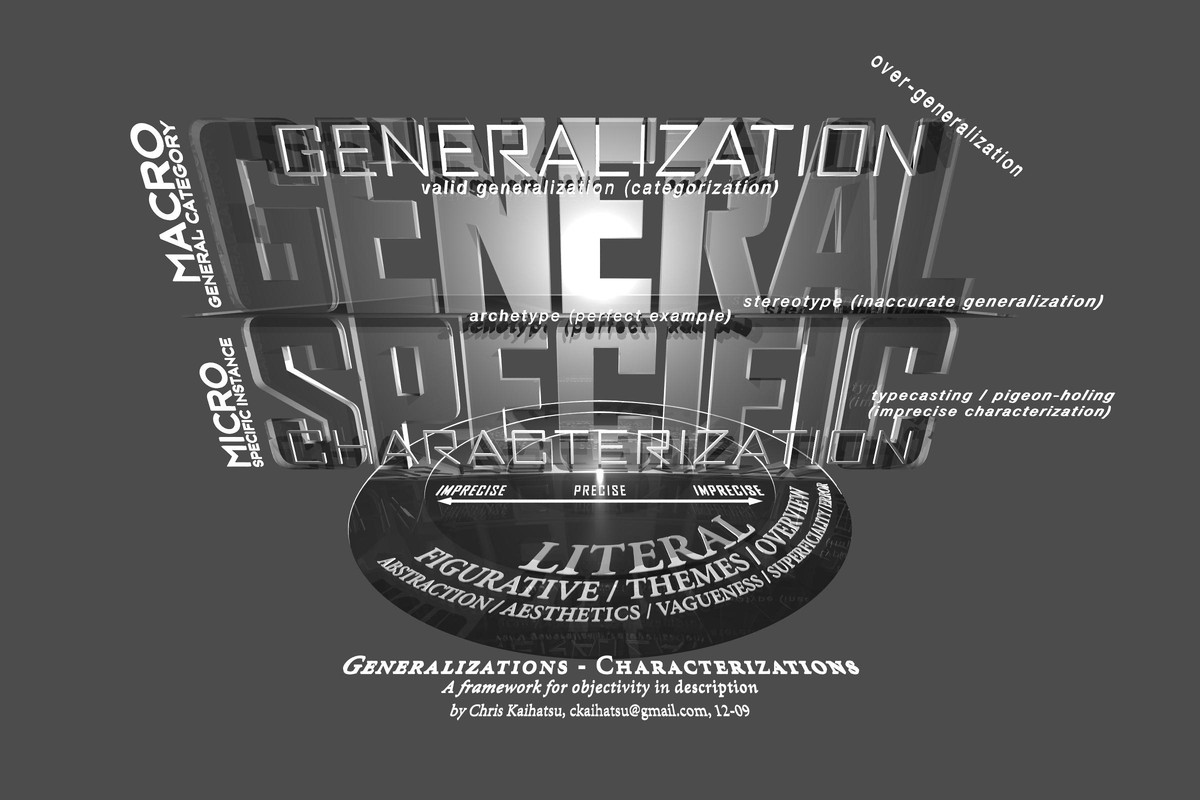

Selecting color as a difference isn't identifying anything essential, a fact can be true but still draw one away from what is the essence of the matter.

If you read those links from Ilyenkov, you might get a grasp of the sort of distinction that is being raised.

Otherwise you will at best reach the point of Kant and still be arbitrary in your logic and selection of features as if concepts are applied externally to the empirical reality.

https://www.marxists.org/archive/ilyenkov/works/essays/essay3.htm

Ricardo's labour theory of value was dismissed for its contradictory character, when in fact he was on the right path. Some contradictions are simply errors in ones reasoning, others are more a reflection of the essential quality of a problem.

It is when one identifies the essential fact, the concrete universal, that one resolved the contradiction. Like how Marx distinguishes labour power from labor, he in fact resolved a a contradiction in Ricardo's work.

Marx also resolved the epistemological dichtonomy between materialism and idealism in following Hegel's emphasis on activity as a substance.

http://critique-of-pure-interest.blogspot.com/2011/12/between-materialism-and-idealism-marx.html

Which is in part how he is able to overcome the tendency to treat value as some purely subjective quality rather than a suprasensous objective thing. He doesn't positindividal man against empirical reality, but treats man as a social being developed out of the whole within a particular place.

And class need not be rigid exactly other than one should get to the essentials, otherwise one ends up in the arbitrary tendency of believing everyone is what ever someone says they are. There can be no resolution if reasoning is arbitrary in its selection of what features are essential.

This lengthy passage illustrates what happens when one identifies the essene as those qualities which are shared by all rather than the particular thing which underpins the existence of all other particulars.

https://www.marxists.org/archive/ilyenkov/works/articles/universal.htm

One finds the genus to all other facts in reality, not merely collecting their shared attributes. Finding that which underpins all others means resolving a contradiction, an opposition because it establishes a logical certainty not found through identifying similarity.

Indeed warfare is destructive, but often peace is only a semblance based on one group maintaining their power over another. Change for many things doesn't come through consensus or simply from above but illiberal struggles in civil society.

Yes, colloquial.

Individuals may have other motives than profit but the logic of the economy compels capitalists to compete and profit.

A capitalist who ceases to do so would not remain one eventually. There is course room in which to not be such an asshole within capitalism to some extent.

Can implement some policies which aren't open class warfare and is sound economically.

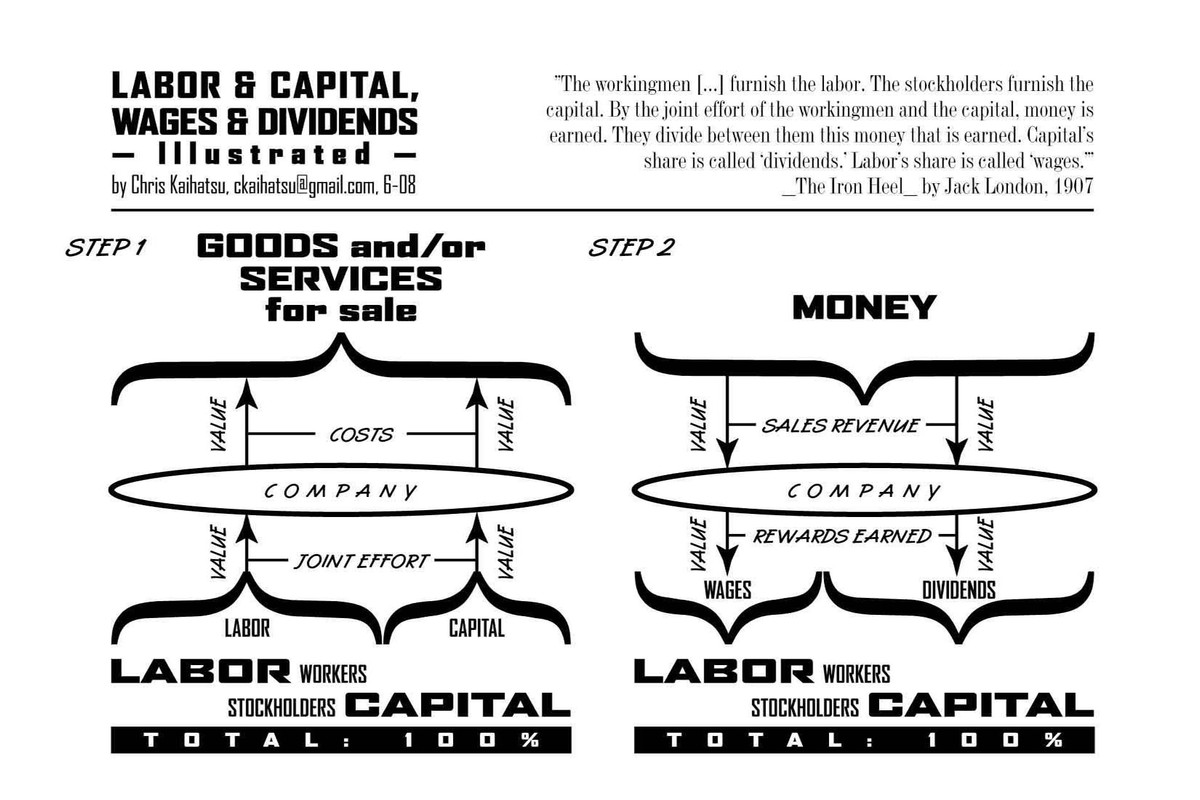

Indeed that is my understanding is that generally profit refers to that of the company which gains although the connotation of it allows it to be used more broadly in looser conversation. But wages are of course not profit qualitatively even while both are money.

Well it is psychological as in it is experienced by conscious human beings, but it isn't psychological in that it doesn't simply originate in the individuals psyche but from social relations. Capiatlists are also considered to experience alienation and alienation isn't unique to capitalism, it is just very intense and generalized. The idea of it also relates to our essentially social nature, as opposed to the abstract individualism typical to the origins of liberalism in which individuals have no real ties to one another except the pursuit of their consumptive desires.

[URL]http://d-scholarship.pitt.edu/10867/1/VWills_ETD_2011.pdf[/ur;]

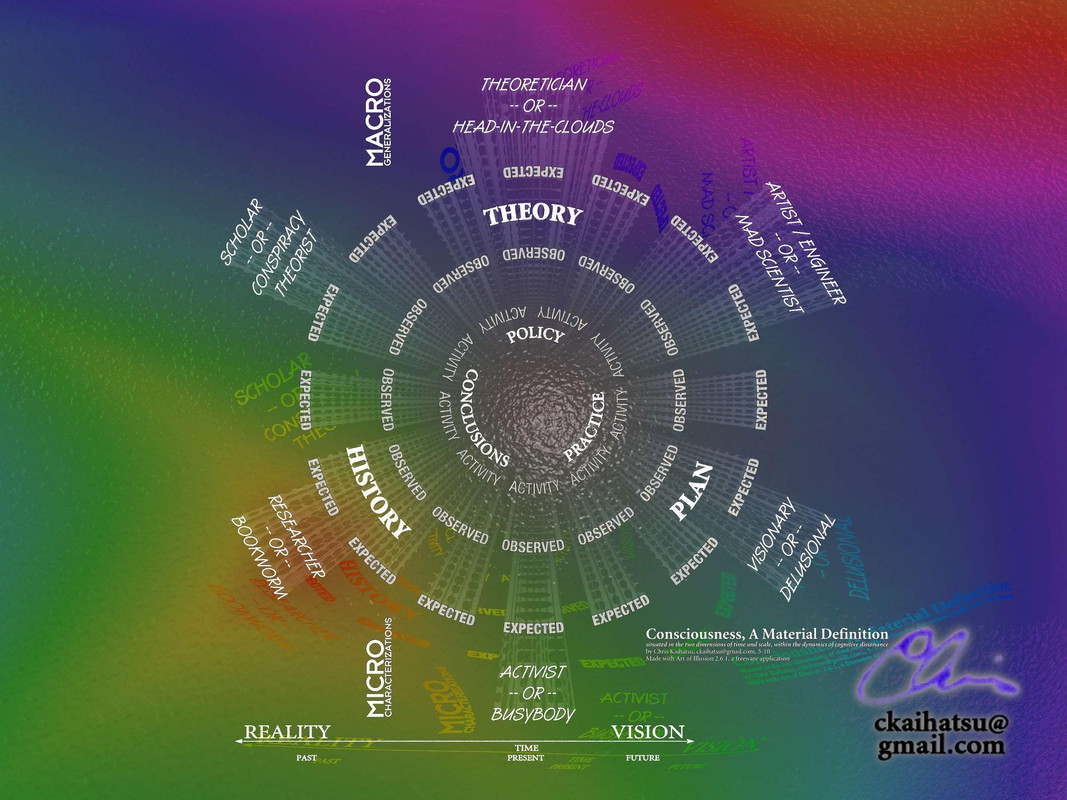

The gist I take away in the above link is that Marx's idea of overocming alienation has to do with making labor directly social and not mediated by commodities where things end up with reified properties based on those relations as if they were inherent to the objects themselves like money having value. Human powers and properties are seen as the property of things and things come between human relations in a way which fragments and distances them.

[/QUOTE]

Well I also contested earlier Roemer's view in which labor isn't a special substance or source of value which then leads him to think that any commodity can be conceived as exploited. Basically he doesn't wish to disginstuish labour-power as a particularly distinct commodity but somehow synonymous with all others.

https://www.politicsforum.org/forum/viewtopic.php?p=15171183

But yes the ethical qualities does arrive in part because objects aren't to be considered as human subjects and in fact there are aspects in which treating someone as an object is wrong without adequate qualifications of how one engages with the materiality of someone but in a way which is acceptable within the norms of society. I mean, slaves as property did exist and were denied any sense of being human. But we of course consider that wrong now for the most part.

I would following the above summary on aleination that the ethical implications of Marx's critique of the political economy is much farther than the mere gap between necessary and surplus labour. His is much more radical than the Ricardian socialist because what informs his critique is the idea of human beings and thus what they ought to be and could be in contrast to how they are.

Except such preferences are abstracted from structural conditions which inform those preferences, hence the above paper which earlier showed how microeconomics was too unstable to be generalized to macroeconomics because it pretty much doesn't explain anything and leaves outside its purview the very relations which may underpin people's preferences. To which there is a distinction between what structural forces inform the preferences of workers compared to that of a capitalist.

https://kapitalism101.wordpress.com/2011/11/15/law-of-value-8-subjectobject/

I would say Marx's value theory for example has a lot to offer in explaining capitalist crisis where others tend to generalize particular aspects and don't have a comprehensive take.

https://critiqueofcrisistheory.wordpress.com/responses-to-readers-austrian-economics-versus-marxism/value-theory-the-transformation-problem-and-crisis-theory/

Marx also has an interesting theory of money in that he marks it as a distinct thing and doesn't simply consider it as a generalization of barter.

https://college.holycross.edu/eej/Volume14/V14N4P299_318.pdf

https://kapitalism101.wordpress.com/2011/09/30/marginal-futility-reflections-on-simon-clarkes-marx-marginalism-and-modern-sociology/

https://critiqueofcrisistheory.wordpress.com/responses-to-readers-austrian-economics-versus-marxism/world-trade-and-the-false-theory-of-comparative-advantage/

One sees how he explains the origin of money having value in commodity production.

I think his identification of labour power, and the essential marker of class (much of his work is built upon that of others into a synthesis so isn't entirely original necessarily) provide a great entry point of analysis which can ground things better than more one sided abstractions that treat individuals in a more abstract manner, not really embedded them in social relations.

I also think marginal utility often conflates what is incommensurate, use value and exchange value. The emphasis on the individuals desire to use something is artbitrarily tied to exchange values of commodities assuming full knowledge of what commodities trade for which is more reflective of a simple commodity exchange unmediated by money. The desire for use values exists across all societies but money as a universal commodity is particular to capitalism. Money predates capitalism but takes time to establish as the universal mediator. So they avoid the issue of money and even value even while they often infer value in models where they assume the equilibrium of supply and demand where the price fluctuations are deemed irrelevant and one considers the value of a thing more directly. Marx adopts the same abstraction to reveal things even while his theory is of nonequilibrium and sees prices following value but coincidentally coinciding with it directly. Political economists of the past have a lot more to explore in the social and political than modern economists who take too much for granted ie are uncritical of the appearences of things. Which isn’t my singular opinion when one takes a view of economics in the long run rather than that confined to the modern marginialists.

[url] https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/821 ... ilosophers[/url

I also think his manner of abstracting puts capitalism in historical perspective rather than generalizing logic of capitalist production back onto the past in representing capitalism as technical expansion of production.

Now there are all sorts of things posd in economics which are true in a sense, they do reflect things which occur in reality and as such aren't somehow automatically dismissed as wrong. Rather I see Marx as not being somehow entirely external and independent of economics but rather critical of somethings as limitations, as foreclosing analysis. FOr example commodity fetishism wouldn't really pop into modern economics at all but it is illustrative of a real phenemon and can help explain other things beyond the economy in fact.

wat0n wrote:Fair point, although for instance a paper-based advertising platform, where you can permanently market a property, would not be a one time thing as just a newspaper ad. I think they could charge you as a percentage of your earnings.

Indeed Airbnb takes a cut from guests and hosts as a commission for bookings, they provide the service of brokering, which is a bit differently than merely advertising as they're trying to directly connect you to the service rather than simply make an appeal to you to use the service. Hence why Airbnb actually pays for advertising and marketing as separate from its app platform as it does need promotion for people to come to the app.

They are not the only ones making profits though. Hosts also make profits in this process (however small they may be), which is why they participate at all!

But this is where I'm trying to drill in a distinction between a contract laborer as distinct from the petty bourgeoisie or small business owner. Contract labor isn't so essentially different from the wage laborer as to not be part of the working class.

Here's a good summary to emphasize what I already did in which wages are pushed down in part because of the competition among workers whose livelihood is precarious.

https://www.marxists.org/glossary/terms/c/o.htm

There is another instance where workers, those who have nothing to sell but their labour power, not only work for capitalists but also succeed in expanding capital, but still they do not sell their labour power and consequently do not work for wages: this is the case with contract labour, such as in the building trades or with out-sourcing in the clothing trades and so on. In these cases, the workers, i.e., those who actually do the productive work, are forced to act as if they were independent economic agents, private labourers, proprietors in their own right. How is it possible that a profit is made here? Whether a builders labourer is paid an hourly wage or is paid by piece work is a secondary question, (see Chapter 21 of Capital). The piece rate is simply so adjusted to keep the worker’s nose to the grindstone struggling to earn a living. It is much the same with contract labour which is essentially the same as piece work.

How does the labour-hire firm make a profit where the independent contract labourer or out-worker remains as exploited and as proletarian as the conventional wage-worker? This raises much the same question as to how any capitalist makes a profit nowadays.

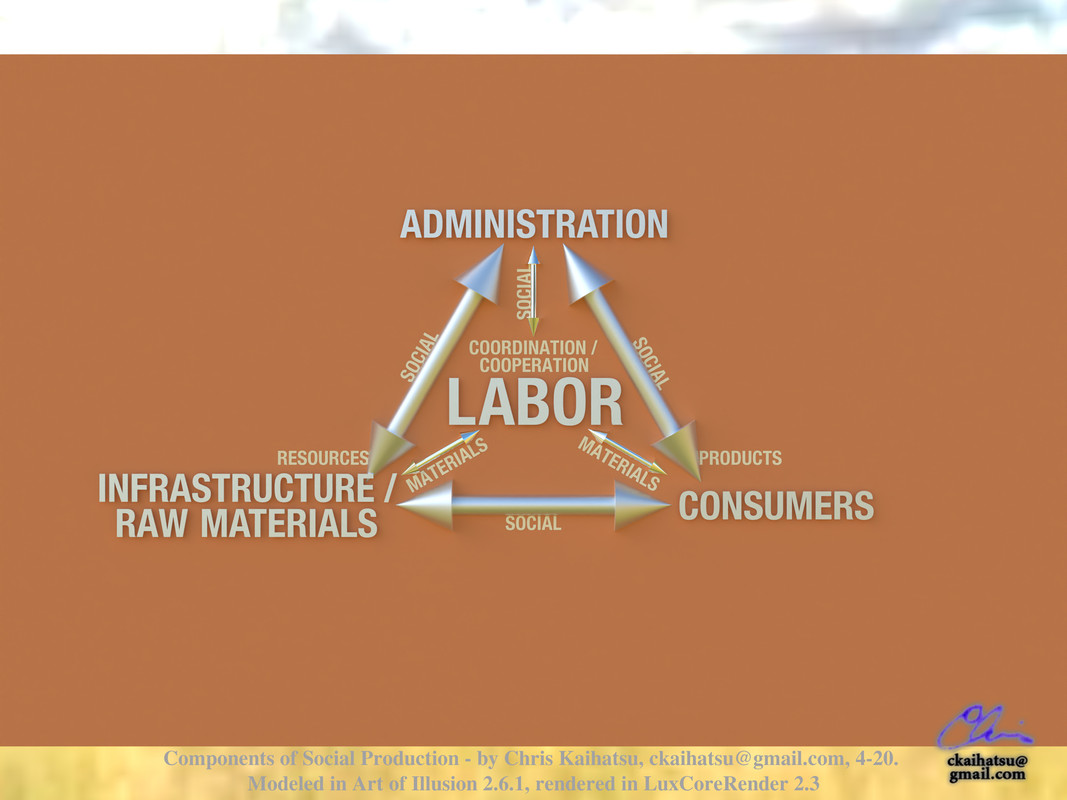

The labourer has nothing to sell but her labour power. The capitalist owns the social means of production as private property. The labour process of our times cannot be carried on as simple private labour; or rather:— the simple expenditure of the labour of an individual labourer which is not socially coordinated, does not produce enough to live on, let alone make a profit for someone. In Marx’s day, the pre-requisite for socially developed labour were the big factories and materials such as steel and coal which were used in the productive process. In order to work at the socially average level of productivity in those days, one had to have access to factories and so on. These were the private property of a class of people called the bourgeoisie, and these people used their privileged position of ownership of these social means of production to exploit those that had no other means of support other than to work in their factories.

Nowadays, most of these factories are either rust buckets, or take the form of temporary set ups in the enterprise zones of Third World countries. But productive work cannot be carried out without a certain amount of this kind of material, including land, buildings, computers, electricity supply, paper and so on, all of which one needs money to buy, and most importantly, there is always a substantial lead time between productive labour and the return coming back, and in order to be socially productive labour will always be complex, involving the coordinated labour of very many people, including not only immediate co-workers, but the vicarious labour of other in the form of software, science, texts, and so on. Even though the ownership of stuff as such is no longer so important to capital, the ability to bring developed social labour to bear is vital to making a profit, to working at better than subsistence level, and for that invariably an accumulation of money is necessary, i.e., Capital.

Now see the above how the direct ownership of the means of production doesn't stop a capitalist still profiting from the work of others. You seem to make no distinction in quality between the person who does all the work themselves in maintaining an airbnb directly in their own home with renting out a room in comparison to the person who has the capital to invest in alternative properties and even hire employees or other workers.

The small business owners in fact have the means to become independent of airbnb.

https://c94e25ea-37c0-4c5f-bd71-5f6fcac47514.Perhaps%20because%20risk%20in%20the%20workplace%20is%20no%20longer%20assumed%20solely%20by%20entrepreneurs%20(Hacker,%202006;%20Pugh,%202015),%20workers%20for%20these%20services%20do%20not%20generally%20view%20sharing%20economy%20work%20as%20entrepreneurial%20unless%20they%20have%20taken%20on%20considerable%20financial%20risks%20(such%20as%20renting%20multiple%20apartments)%20and%20hiring%20other%20workers.%20In%20some%20cases,%20such%20as%20with%20Kitchensurfing%20chefs,%20sharing%20economy%20work%20was%20viewed%20as%20part%20of%20a%20marketing%20effort%20for%20a%20separate%20company%20outside%20of%20the%20so-called%20sharing%20economy.%20filesusr.com/ugd/e5771f_112374073d3d403f92f5ebab52170590.pdf

Rather than serve as a novel on-ramp to entrepreneuralism, workers who succeed in the sharing economy - such as multiunit AIrbnb hosts and Kitchensurfing shefs with side busiiness - often have significant skills or capital that would also enable them to succeed outside the sharing economy. In addition, successful workers often strive to leave the sharing economy behind by creating firms that offer the benefits and protections of employment, not independent contracting.

This point of the relevative independence of those who use Airbnb to host multiple units and their ability to actually work independently of airbnb if they so chose, to me emphasizes a distinction between them an what may count as employees in the case of those who do all the work themselves. They provide their own personal home space, they do the cleaning and so on.

Consider this piece which argue that under California law currently, Airbnb hosts would be considered independent contractors, but with their proposed ABC test, they would fail to be considered as such.

https://poseidon01.ssrn.com/delivery.php?ID=004020091089127119019087003092003075120015077012021005105006110113075120101113096030041107053119007034112080088111123066030005053026022082043007070010115071077100090015042078014124113094026075120100102104003108121110093004070120013097119011082097017&EXT=pdf&INDEX=TRUE

1. Part A: Airbnb’s Control

While Airbnb does exert some control over its hosts—such as monitoring their performance through ratings and handling all billing, dispute resolution, and refunds153—a comparison between Uber, Lyft, and Airbnb demonstrates that Airbnb’s exercise of control over its hosts is not nearly as extensive as that exercised over drivers by Uber and Lyft. While Airbnb does monitor host performance through ratings, it does not directly engage in selecting guests for hosts (and hosts for guests) the way Uber and Lyft select passengers for drivers (and drivers for passengers).154 In addition, Airbnb does not set the price of the service, as Uber and Lyft allegedly do.155 An argument could be made that Airbnb’s level of control is limited to what is necessary to achieve the result—a short-term rental satisfactory to both the host and the guest— versus the manner and means by which that result is achieved.156 If an examination of Airbnb’s classification of hosts as independent contractors were limited to the “traditional” control-based classifications tests,157 then Airbnb’s hosts would most likely be considered properly classified as independent contractors. However, under the ABC test, two additional elements must also be satisfied.

2. Part B: Airbnb’s Usual Course of Business

Under Part B of the ABC Test, workers are presumed to be employees if they do not perform work that is outside the usual course of the hiring party’s business. Another way to consider this issue is whether the workers in question are integral and essential to the hiring business.158 Airbnb is an online platform-based business connecting hosts with guests, while Uber and Lyft are online platform-based businesses connecting drivers with passengers. As we have already seen above, courts have dismissed almost out of hand the argument that Uber and Lyft are mere technology companies and not transportation companies (meaning drivers are providing services within the companies’ usual course of business).159

Platform-based businesses argue they are merely a technological intermediary connecting someone seeking services (a ride or room) with someone providing that service (a driver or host).160 In addressing whether Amazon.com can be held strictly liable for injuries arising from a defective product sold on its website by a third-party vendor, the Court of Appeals for the Fourth District of California rejected Amazon.com’s argument that it was merely a technological intermediary connecting a consumer with a thirdparty seller.161 The court’s perspective is instructive: Amazon.com constructed the website that marketed the product in question and accepted payment for the product from the consumer, then paid the vendor after deducting fees. In other words, it stood between and controlled the transaction between the consumer and vendor.162 Similarly, Airbnb stands between and controls the transaction between the consumer and the host.

Are hosts an integrated and essential part of Airbnb’s business? In other words, without hosts, would Airbnb exist?163 To paraphrase the U.S. District Court for the District of Massachusetts (applying that state’s ABC Test, Part B), the realities of Airbnb’s business—where travelers pay Airbnb for short term rentals—encompasses the hosting of travelers.164 The question appears to have been partially answered by the economic fallout of the COVID-19 pandemic. As a result of decreased booking and cancellations, Airbnb saw its revenues drop precipitously and laid off internal employees.165 If Airbnb cannot survive without its hosts supplying accommodations to guests, hosts are arguably an integral part of Airbnb’s business.

3. Part C: Airbnb Hosts’ Independently Established Trade, Occupation, or Business

To be considered an independent contractor under Part C of the ABC test, the service provider (i.e., Uber driver or Airbnb host) must be customarily engaged in an independently established trade, occupation, or business in the same nature as the work involved.166 As previously stated, to meet this requirement, courts have held that the worker’s “business” must be able to persist if the relationship with the platform ended.167

Once again, the economic fallout of the COVID-19 pandemic may hold a potential answer to this issue. On one hand, many Airbnb hosts act like independent businesses, maintaining short-term rental properties at such a high caliber and frequency that they qualify for “Superhost” status.168 Now, many Superhosts—who took out significant debt to purchase prime real estate to list on Airbnb—are suffering economically.169 Fundamentally, the pain associated with the pandemic fallout is being felt by hosts as much as by Airbnb’s laid off employees.170

Will hosts who purchased properties be left in a similar state of financial ruin as an employee who loses his or her job?171 Congress evidently thought so by including “Pandemic Unemployment Assistance” in the CARES Act.172 One could argue that treating Airbnb hosts and Uber and Lyft drivers the same under the PUA would not necessarily mean they are all properly classified as self-employed independent contractors, but rather are misclassified entirely and need the same unemployment benefits as “traditional” employees

...

while Airbnb hosts would probably not be reclassified as employees under a “traditional” control-based test, they could very well be reclassified under the ABC Test. Airbnb hosts might actually be considered employees because they are both integral to Airbnb’s business (i.e., Part B is not met) and not necessarily independent businesses themselves (i.e., Part C is not met).

I imagine you and others might emphasize part 1/A, that the lack of such direct control by Airbnb emphasizes how they're not workers but truly are independent. This is certainly a defensible advantage for Airbnb as compared to other platforms for the gig economy and I felt was a weak point in some earlier criticisms. However what does resonate are the other two points which follows from my above points about the relative independence of the individuals to work separately or outside airbnb or not. Those who are solely dependent on airbnb bringing the market to them are more likely to be considered employees while those who have carved out a niche for themselves outside or it or could readily do so and are even close to doing so such as the aspiring hotelier, are more distinctly small business owners.

The article itself seems to go even further to emphasize that those who I would perhaps see as closer to being small business owners are not as such if they remain entirely dependent on the airbnb platform, they are markedly not independent enough to be considered independent contractors but are employees essential to Airbnbs business model.

Hold on, what makes you believe people start businesses out of leisure?

The way I see it, at least, is that they do it because they are more profitable - adjusted for risk and discounting future flows - than the alternatives. Likewise, workers also don't start businesses for the same reason, as you mention you for instance value stability - but there are those who don't, and are more willing to take risk if the payoff is good enough. Because, yes, starting a business is far from a safe bet, at all.

Perhaps a different issue lies with people who inherit an already established business. But even they are taking risk, in this case the risk that comes with having to make all the major decisions and where if you mess up, you'll have to face responsibilities for it.

This is not to say, of course, there aren't businessowners who don't intrinsically love what they do. But there are also workers who intrinsically love what they do as well.

I didn't generalize all interests in starting a business as motivated by leisure but emphasized the interview aspiring to a point of profitability that it became a passive income.

Do you think passive income doesn't exist for those who have ownership and do not have to be so actively involved in their business as they delegrate to employees?

Also lost in your emphasis of merely taking financial risks is also the ability to even take such risks, that is to have such money in order to invest it as capital in the first place. Some people may qualify for loans but plenty don't because their situation doesn't allow great confidence in their ability to pay it back and so is too much risk for those who give out the loans.

The quote on the interviewees emphasizes how they have the skills and capital to pursue a business outside of airbnb. That can be the same aspiration for employees of course, as mentioned, that basically are workers in a extremely precarious situation and thus end up in contract work.

But thinking of the skilled contractor, they tend to be distinguished also in the fact that they sell private labor and as such do have relative independence due to the demand of their skills.

https://www.marxists.org/glossary/terms/c/o.htm#contract-labour

This form of wage labour, however, denies the worker any continuity or security of employment because every contract, be it for a day or a month, is a distinct contract of sale. Since the pretence is that the labourer is an equal economic agent, the worker is usually responsible for their own social-security payments, and must put aside money to pay tax and for their own retirement etc. It may very well be the case that the worker “hires” some fellow workers and lifts themselves up to the position of a kind of leading-hand or overseer, and indeed there may be a continuous scale from the most oppressed day-labourer up to a small-scale capitalist providing day-labour and earning a good living, not unlike the Triads who supply day labour for the Japanese corporations (see Toyotism). Small service-providers, consultants, self-employed “change managers”, etc. who are hired on contract are not generally referred to as “contract labour”, since in their case they are genuinely petit-bourgeois engaged in the sale of private labour.

Here again I think you're trying to emphasize sameness in order to disrupt any distinction between a worker and petit-bourgeois. Instead of emphasizing the precariousness, it all gets subsumed under risk of investment. The idea here that workers are simply taking a risk for the prospect of more 'profit'.

Which again I think is muddying the waters a bit like how one might frame all of prostitution in terms of women who have the means to voluntarily leave the profession compared to those who are coerced into it out of poverty or what ever. As if they're the same person. So to the person who can't find stable employment and is pressed into the gig/sharing economy is equated with the same people who actually succeeded at airbnb in starting up the basis of a small business with airbnb as a starting point to tap into the market.

I would not be so sure that regular people renting a room aren't making a profit either - it's a small complement to their usual net income (net of taxes and costs to work their regular jobs such as commuting), of course, but just what costs are they taking on, really?

Airbnb hosts can't simply state there is a room available, they have to appeal to the taste and expectation of their customers to be competitive.

https://www.cnbc.com/2019/07/03/is-running-an-airbnb-profitable-heres-what-you-need-to-know.html

“You have to realize everything should be furnished and it should be fairly new because you are competing with other Airbnb hosts,” Weber says. He pegs the cost at roughly $1,500 per bedroom, plus another $2,000 to $3,000 for the rest of the house and common areas. Which is on par with other experts’ estimates.

Even if you’re not looking to become a superhost, there are some basic equipment that Rusteen recommends investing in:

- a digital keyless entry system to make it easy for guests to access your place remotely (without losing the keys)

WiFi and, depending on the size of your apartment, a WiFi network extender

- a SmartTV

- extra towels (the more you start with, the less frequently you’ll need to do laundry)

toiletries such as shampoo and soap

- pantry staples such as salt, pepper and condiments.

Of course, you could provide many more amenities — from ironing boards to wine openers. Many times, you may need to feel it out and add items as needed by your guests.

“It’s all about acclimating your guests to their new environment, aka your Airbnb listing, as quickly as possible,” says Rusteen, who now manages several properties in the U.S.

Photos can be another way “to set yourself up for success,” Rusteen says. “One of the first things you should do as a host is get professional photographs.” You can expect to spend $100 to $200, on average, for a session. You can actually find photographers for this through the Google Street View professional program.

You can get by without spending a lot to redo your space. Miller, who wrote a book on her experiences, says she spent very little, but she did put in quite a bit of time and work.

“We fixed things that needed fixing, put locks on some cupboards and on the office (so we could lock away valuables), and created a household information folder,” she says.

So it’s important to keep in mind that you will likely put in money or your time, or both, to prepare to rent out your space.

...

Additionally, make sure your insurance covers your new venture. Mistakes happen, so it’s important to think ahead. The big companies such as Airbnb, Homeaway and Vrbo provide liability insurance that covers up to $1 million, but there are restrictions and it can be a challenge submitting claims.

“Anything below $50, just pay it out of pocket,” Rusteen recommends.

If you are worried about being left with a bill for some expensive accidental damage, Rusteen and Weber recommend purchasing short-term rental insurance. And before you start accepting guests, it’s a good idea to read through the fine print of your existing homeowners’ or renters’ insurance policy. Some policies have stipulations that extra renters can negate your entire policy.

Overall, whether you choose to get extra insurance depends on the level of risk you’re comfortable with. Miller discovered that, for her situation, getting home insurance for Airbnb rentals was extremely difficult and costly. Instead, she took the approach of minimizing risk by thoroughly screening her guests and asking for a security deposit.

They basically need to be like a hotel in their services except the host pays for this all upfront, so they need the sort of cash to be able to supply all this. And see how the money saver comes in the form of putting in your own work.

Now the host takes on the risk, puts in the investment and does all the work, but focusing on the earlier quotes, while airbnb doesn't own anything, the person works for airbnb as they are not independent workers who happens o contract with airbnb but are entirely dependent on airbnbs brokering as is airbnb dependent on the host doing all the leg work. They effectively socially coordinate the work which is a prerequisite for them to actually make some money, which they cannot do without airbnb and if they can then they are more distinctly an independent contractor rather than an employee who has to to not only work but bring in the materials, land and so on necessary for the work. A bit like how workers aren't invested in being trained anymore but have to take that as a personal cost, more and more is shifted back onto workers so as to put risks and costs back on individuals and to not detract from profits and make all the more precarious workers as in an unregulated labor market.

Well, often people will actually start businesses with a good idea precisely so some big fish will buy them off, letting them instantly make a huge profit. This of course doesn't work all too often - most startups fail - but if you hit the jackpot you do it big time.

Indeed, its a lucrative risk to take.

Indeed, although the flipside is that if you do away with it current hosts and guests lose as a result of ending this market. I actually think that the issue isn't so much AirBnB but broader problems in so

Here you would seem to be agreeable with the above points of how the hosts are not independent of airbnb's platform and may not necessarily have the means to be as such if the market for them ends with the lack of airbnb.

Indeed the broader problem being the contradiction between exchange value and use value, there is great need but effective demand is what matters in the economy.

https://critiqueofcrisistheory.wordpress.com/crisis-theories-underconsumption/

The underconsumptionists point out, correctly, that if capitalist production was production for the needs of the workers, there would not be any crises of overproduction. Capitalist overproduction is overproduction of exchange values, not overproduction of use values. A crisis of overproduction of exchange values breaks out when there is still very much an underproduction of use values, especially use values that the workers themselves need.

However, Airbnb is just par of exacerbating this issue in which human needs become increasingly detached from exchange value. YOu end up with people unable to find housing because there is more money in the short term. See an issue with CHinas use of real estate as investment properties for their wealth which leads to all sorts of unused homes because its about money, not use.

Indeed, there needs to be some regulation for sure but there are tradeoffs involved, particularly when it comes to zoning. Sure, you can have strict laws and keep your quality of life (with reduced density) but it comes at the cost of ever increasing property prices. And of course, you can densify like crazy if you want to have cheaper property prices but you'll have to deal with the quality of life costs that comes with it.

I don't think there are free lunches here, AirBnB would justify reform simply because it did not exist when these regulations were drafted and hence some adjustment would be warranted.

Construction standards are a different matter, I think, and I fully agree with having demanding standards in all. Nowadays it seems the bulk of a property's costs comes from land, at least in large cities, not the structures themselves anyway.

Indeed, New York and all major cities are ridiculous because of the high demand for the small space. I actually enjoy living in a small town where I can afford a decent sized home for a much lower price and works out well having an education and access to the few decent paying jobs here.

Indeed regulations have to be introduced for the changed market to try and balance out some of the effects within some tolerable range. Just like how many hosts are treated as independent contractors as opposed to employees.

Indeed, and I agree that it's not great. But I can imagine people that definitely benefit from Uber, for instance I can imagine a single mother of 3 probably preferring to Uber or to be an AirBnB host over working on a rigid schedule, mostly because of the kids, if she made the same.

Honestly the way to think about the gig economy is more about the options and flexibility it offers than anything else. And it comes with a cost, namely, that you take on more risk than on a more traditional wage work arrangement. So at some point, it's up to how much you need or prefer flexible arrangements over rigid but safer ones.

Indeed women being primarily tasked with dependents results in them adopting more flexible jobs, and more flexible jobs such as these of course means higher risks, lower pay and so on.

Which is exactly why it benefits businesses to mark them as independent contractors as opposed to employees with what labor laws exist having applicability.

https://www.jacobinmag.com/2015/05/freelance-independent-contractor-union-precariat/

But It’s Voluntary!

Are freelancers pushed or do they jump? Does it matter?

People freelance for many reasons. Some really are in it for fortune and glory, as the stereotypes about carefree millennials would have it; the Freelancers Union survey found that many respondents had chosen freelance work and were happy with that choice.

There is no question that not having a boss has a great deal to offer: no office politics, no pantyhose, no sexual harassment from lecherous supervisors, no fetching anyone coffee, no commute. Freelancers also have the right to turn down projects, though that freedom of consent is contingent upon an abundance of work.

As appealing as these features are, though, they are not necessarily the material drivers of the decision to freelance.

A very large chunk of freelancers work as independent contractors because their industries have restructured, eliminating fixed employment and job security. In publishing and print media, for example, writers, editors, designers, and other media professionals now freelance because the industry is structured around a heavily exploited skeleton crew in the office and a reserve army of freelance labor to be subcontracted at will.

Others freelance because their industry restructured before they got there, or was created around the reserve-army model to begin with. This is particularly the case for younger workers in tech and digital media, where the kinds of stable jobs that Guy Standing would consider the jobs of the “true proletariat” never existed in the first place.

Finally, there’s a category, often underestimated, of workers who are forced into freelance work because the conditions of traditional employment have squeezed them out by refusing to accommodate workers’ basic human needs, like sick days and parental leave.

The Family Medical Leave Act, which allows some workers to take unpaid maternity leave, applies to less than 10 percent of all employers; the US and Papua New Guinea are the only countries in the world that do not guarantee any maternity leave by law.

According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, approximately 75 percent of full-time US workers and 27 percent of part-time workers have some paid sick days. The average full-time worker with a tenure of less than five years — the average length of employment — has eight to nine days of paid sick leave per year. This time may or may not also include vacation days, since many employers prefer a policy of “paid time off” to be used for illness or vacation.

Parents (particularly single parents) and people dealing with disabilities or chronic illness are faced with a choice: work sick and forgo needed medical care for themselves and their children, or face being fired under their employer’s attendance policy. If you can’t get disability or can’t afford to be a stay-at-home parent, the only choice left is freelancing. More than 40 percent of respondents to the Freelancers Union survey listed schedule flexibility as a primary motivation for freelancing.

Given that the burdens of child care and elder care are disproportionately placed on women, the gender balance of the freelance workforce is highly skewed. I recently attended a conference for freelance editors at which more than 75 percent of the attendees were female.

Surprisingly, recent Bureau of Labor Statistics findings show that the wage gap for women, which is 77 cents on the dollar for white women and as low as 51 cents for black and Latina women, appears to be mitigated or even eliminated in the freelance world, depending on other factors such as race. This suggests that some workers may calculate that employer discrimination makes the situation so impossible that they are better off fending for themselves, outside formal employment.

So can these workers be said to have jumped, or were they pushed?

So basically it takes advantage of the structures in which women's responsibilities compel them to look for such flexibility.

The dynamic being that dependents aren't well supported within capitalism and those who receive the most support often are those of the higher wages/incomes.

https://www.ethicalpolitics.org/ablunden/pdfs/social.pdf

Let’s make a metaphor with the issue of women living in a location in the division of labour as unpaid child-carers; think of “women’s work” as a neighbourhood, and women as people living there, some by choice, some against their will. What options are available to women in this space?

One option is increased child benefits for stay-at-home mothers, thus making life better in the ghetto, a measure welcomed and immediately benefiting people stuck there. It also has the effect of marginally enhancing the status of child-carers, but it is hardly likely to enhance the attractiveness of being a stay-at-home parent sufficiently to encourage men to give up their paid work and become househusbands. It actually emphasises a woman’s role as unpaid child-carer, trapping her in that role, since it is a disincentive to going out to get paid work, stigmatises the mother as a welfare recipient and relieves the male of responsibility for contributing to the upbringing of his own children. This is the kind of affirmative strategy which has immediate appeal but fails to solve the problem, and correspond to all those kinds of public policy strategies that are based around providing services to “areas of special need.” Good and necessary up to a point, but unable to resolve the underlying problems.

Another strategy is to commercialise child-care, thus moving the job into the market and giving women the choice of doing the same work for a wage, or doing a different job while their own kids are cared for in a childcare centre. This is probably more effective in giving women a choice, but it runs into a couple of problems. So long as child-care is stigmatised as “women’s work,” then it remains low-paid and women move out of their homes into lowpaid jobs doing “women’s work.” There is no way out of this trap until the gender division of labour is broken down. Once women are recognised capable of the same kind of work as men, then women can command wages equal to their male partners and make working for a wage worth putting the kids into child-care. Meanwhile, with child-care no longer stigmatised as “women’s work” she is more likely to be left a fair share of domestic duties and child-care centres are treated as seriously as other service. In other words, the “location” — “women’s work” — has to be deconstructed altogether, and “woman” no longer a socially constructed location.

...

However, childrearing is an important social function. It ought not to be an occupation which

is denigrated and no-one should be forced to go into the professional by reason of their

gender, but whoever is there needs to do the job well. If women choose not to be childraisers, then that has to be a matter of choice, not because they have to go out to work and

“can’t afford children.” If we want the next generation to be raised well, then social

arrangements have to be made to make it a worthwhile profession.

Making “women’s work” everyone’s responsibility, means getting men to take on that work

and that generally means a fight for those stuck with “women’s work” not so much to change

themselves or get better recognition for what they do (these too) but to get other people to

accept their responsibility.

Even when one seeks childcare in the paid form its still low and if it isn't low it's simply not affordable for many and negates the point of even going to work.

Flexibility is always appealing but as you recognize it of course entails other costs rather than it being something built into the structure of society to support families.

It's not simply a preference for flexibility, one has to actually consider what are the structural relations which dictate one's opportunities? It is easy to frame workers as all purely voluntary and such and without any coercion under the way in which structural relations of class and so on are made absent in a lot of descriptions of economics.

Touching upon things but not really relating them within the social context all that much, things are just taken as a natural given because there is a kind of naturalization of capitalist production and relations. However it is contestable.

https://kapitalism101.wordpress.com/2011/09/30/marginal-futility-reflections-on-simon-clarkes-marx-marginalism-and-modern-sociology/

Marginalism can abstract away all of society from economic theory because of its claim that capitalism corresponds to a formal rationality rather than a substantive rationality. Formal rationality is a purely technical calculation of means and ends as opposed to substantive rationality which is oriented around values or higher aims. For instance, in Human Action Mises claims that the basis of economics is the natural quantitative relations between objects… so much input can produce so much output, etc. For marginalism any constraints or limits to the system are purely technical, a result of natural scarcity in relation to our timeless wants, not social, and the market is the best mechanism for organizing these desires. This means that the marginalist model will fail if it can be proven that capitalist institutions have a ‘necessary substantive significance in subjecting individuals to social constraint’. In other words, if the limits and constraints of our society can be shown not the result of technical aspects like scarcity but rather the result of social institutions with particular values oriented toward the interests of certain groups of people (ie the capitalist class) than marginalism has not justification for its formal rationality, for its abstraction of society from economics, and the entire edifice of marginalism falls. It is not enough just to point to this abstraction as proof of the ideological nature of marginalism. We have to prove that it is an illegitimate abstraction. This is the common thread underlying all of Clarke’s specific critiques of different aspects of marginalism. (3)

Marginalists begin with the isolated individual making choices in a vacuum and erect all of their basic ideas upon some simple observations about these choices. As the model becomes increasingly complex, adding in more people, more commodities, money, the division of labor, private property, etc. it is claimed that all of their basic observations still hold. The expansion of the model is seen as just a formal matter. But Clarke argues that when we move from individual exchange to a system of exchange we are actually dealing with different phenomenon. In a market economy exchange is no longer and exchange for direct utility; in other words, we aren’t measuring our actual utility for the commodity we give up with the utility for the commodity we buy. Money intercedes as a mediary. We exchange things against money. Use-values are exchanged for values which are socially determined. Any claim to the formal rationality of the individual’s behaviour becomes dependent upon the rationality of the system as a whole.

...

In abstracting away the social relations of capitalism marginalism must assume that these abstract individuals enter exchange with given needs and given resources. Where do these needs and resources come from? The marginalist answer is that this question is outside the sphere of economics- that it doesn’t matter to economic theory where these needs and resources come from. But what if our economic system actually reproduced these needs and resources? If we could show that capitalism produced the hedonistic consumer as well as the conditions of scarcity the consumer confronts then we could expose a disastrous feedback loop at the core of marginalism. It seems that when we just assume given needs and resources we are actually only pretending to abstract away from capitalist social relations. While on the surface marginalists appear to be talking about a universal individual in universal conditions, in actuality they are sneaking all of the social relations of capitalism in the back door. This is very similar to the Bukharin critique I mentioned a few weeks ago.

I like the way Clarke develop his proof this problem: Commodity exchange presupposes individuals with different needs and different resources because if everyone had the same stuff there would be no reason for exchange. Thus exchange presupposes differences. If exchange is systematic these differences must also be systematic. Thus the formal equality and freedom of exchange is founded on different resource endowments. This means that the content of exchange can’t be reduced to its form (free, juridically equal relations between people) but must be found outside of exchange in the realm of production and property.

Scarcity relates to the application of labor to produce for need. The basis of exchange is the sale of the products of this labor. Thus the need for a theory of value based on human labor, not subjective whims.

Different types of exchange presuppose different production and property relations. The simple commodity exchange (independent producers exchanging the product of their labor in the market) is a popular image in marginalist accounts of exchange (as well as market-anarchism fantasies) yet such a system of exchange has only existed within larger societies dominated by other social relations (ie feudalism, capitalism, state-capitalism/20th century communism). Capitalist exchange presupposes social relations between two social classes, one owning the means of production, the other nothing. As we’ve seen, Marginalism tries to treat all factors of production with the same theoretical tools of subjective preference theory. But the division of the social product into rent, profit and wages actually presupposes antagonistic social relations between classes and thus requires different theoretical ideas.

Marginalists would like to treat the unequal resource endowments of individuals as due to extra-economic factors, consigning these concerns to the fields of history and sociology. But these inequalities don’t just proceed exchange historically. They are actually reproduced by exchange. Capitalism generates a world in which individuals must maintain a certain standard of living in order to survive (try paying the bills without a phone, house, car, work clothes, haircuts, health-care, etc.) and must engage in wage-labor. And wage-labor actively reproduced the two social classes of capitalist and worker and their violently divergent relationships to the means of production. Without scarcity we couldn’t have wage labor. There would be no reason to work. Thus capitalism must constantly reproduce scarcity.

Basically, there is much to question in the way in which some presentations of decisions of people as many simply take what is at face value and do not critique it. A bit like how one might go well women earn less because they don't get the higher paying jobs, why? Because they choose to enter into more flexible lower paying kinds of work in order to care for dependents instead of pursue their careers. Why is that? Well their decisions are made within a social context and only make sense when related to the social whole because individual actions are nonsense confined to only the individual.

https://aifs.gov.au/publications/family-matters/issue-86/persistent-work-family-strain-among-australian-mothers

In conclusion, Australian mothers in recent decades have greatly increased their participation in the labour market. Fathers, however, have not increased their participation in unpaid household work to a matching degree. But, without equal sharing of the dual roles of earner and carer between mothers and fathers, mothers will inevitably feel the work-family tension more keenly. Furthermore, institutional and structural changes supporting mothers' increased workforce participation are few and slow coming. Consequently, working mothers faced with the challenge of reconciling family and work commitments are often forced to find individual solutions. However, work and family life balance is not a problem specific to individual families. Rather, it is a universal problem shared by many families, and as such it requires institutional and structural changes supported by society as a whole.

https://scholarcommons.scu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1048&context=phi

It is true that actions are carried out by individuals, but such actions are possible and only have meaning in so far as they participate in sociocultural practices. There are two important questions here, Westphal suggests: (1) are individuals the only bearers of psychological states, and (2) can psychological states be understood in individual terms? Individualists answer both questions in the armative, and most holists answer both questions in the negative. Hegel, however, answers the rst question armatively and the second negatively. In other words, it is only individuals who act, have 108 intentions, construct facts, and so forth. Nevertheless, such acts, intentions, and facts cannot be understood apart from sociocultural practices—their meaning can only be understood as interpreted in a sociocultural context.

This is seen in the limitations of microeconomics when expanded to macroeconomics.

http://frankackerman.com/publications/economictheory/Interpreting_Failure_Equilibrium_Theory.pdf

Instability arises in part because aggregate demand is not as well behaved as individual demand. If the aggregate demand function looked like an individual demand function ± that is, if the popular theoretical ®ction of a `representative individual’ could be used to represent market behaviour ± then there would be no problem. Unfortunately, though, the aggregation problem is intrinsic and inescapable. There is no representative individual whose demand function generates the instability found in the SMD theorem (Kirman 1992). Groups of people display patterns and structures of behaviour that are not present in the behaviour of the individual members; this is a mathematical truth with obvious importance throughout the social sciences.

For contemporary economics, this suggests that the pursuit of microfoundations for macroeconomics is futile. Even if individual behaviour were perfectly understood, it would be impossible to draw useful conclusions about macroeconomics directly from that understanding, due to the aggregation problem (Rizvi 1994, Martel 1996). This fact is re¯ected in Arrow’s onesentence summary of the SMD result, quoted at the beginning of this section.

The microeconomic model of behaviour contributes to instability because it says too little about what individuals want or do. From a mathematical standpoint, as Saari suggests, there are too many dimensions of possible variation, too many degrees of freedom, to allow results at a useful level of speci®city. The consumer is free to roam over the vast expanse of available commodities, subject only to a budget constraint and the thinnest possible conception of rationality: anything you can a"ord is acceptable, so long as you avoid blatant inconsistency in your preferences.

The assumed independence of individuals from each other, emphasized by Kirman, is an important part but not the whole of the problem. A reasonable model of social behaviour should recognize the manner in which individuals are interdependent; the standard economic theory of consumption fails to acknowledge any forms of interdependence, except through market transactions. However, merely amending the theory to allow more varied social interactions will not produce a simpler or more stable model. Indeed, if individuals are modelled as following or conforming to the behaviour of others, the interactions will create positive feedback loops in the model, increasing the opportunity for unstable responses to small ¯uctuations (see Section 5)

This is in part why things like class are fundamental, because people aren't abstractly all the same individual making similar decisions. They are subject to different constrains and the constraint of someone who is working class is fundamentally different to that of other classes. As such, one can be critical of the way in which one might try to present workers as the same as other classes in a superficial way. Hiding the coercion of how they're compelled to work to meet their livelihood compared to that of a capitalist.

Indeed, here there are tradeoffs too. But Uber and AirBnB not also help with matching but with monitoring quality to some extent.

And people are often happy to trade off lower cost for less quality control.

Although it seems as pressure has mounted, Airbnb has become on par in cost with Hotels.

https://www.washingtonpost.com/travel/2021/05/25/airbnb-fees-cleaning-hotels/?outputType=amp

So it's losing that cost advantage perhaps.

Hmmmm, I think both go hand in hand here. Along with risk taking, which is another feature of capitalists...

I also would distinguish between the small business owner and capitalist in terms of risk as a lot of risk for capitalists does not destroy them financially as it does the small business owner who in the long run have a tendency to return to the proletarian class. When one thinks of the losses incurred on Airbnb, they cut those loses by cutting off workers and so on.

https://www.wired.com/story/airbnb-quietly-fired-hundreds-of-contract-workers-im-one-of-them/

Who is hurt more here, the company owners or the workers?

BUt of course there is a tendency to generalize the small business owner who invests what little excess wealth they have into risky ventures in the hopes of establishing something bigger for themselves like the guy who aspired for a passive income.

Again, a millionaire may take a gamble on something but how much it really hurts them personally as the company owner is distinct in its nature to that of the worker or small business owner.

What relevant real world economic phenomenon is missed by not taking the class distinction into account?

You say that both are different, and indeed it's different. But for example a red and a green apple are different too. So... what's the practical importance of that difference, even more so when class is far from being as rigid as it was 150 years ago?

Well for example one is pretty much making untenable the idea of exploitation of labor and thus the very theory of value. If there are no classes, then the presentation of people as simply equal agents on the market abstracted of their structural relations makes equality of the market seem natural and self evident. Everyone is on par with one another. But as mentioned earlier in simon clarkes critique of marginalism, that the different resource ednowments must be structural if they're to be ongoing and one must look to property and production relations to actually find that labourers are a distinct class from capitalists when they come to the market for exchange of their labour power. And they are coerced into such work by the structural deprivation of any means of subsistence, they have to work to survive. Without such a structural relation, capitalism would not have a means of forcing productivity and intense measures upon the working class.

It's whether the difference marks an essential point of their real attraction to one another. Workers and capitalists are brought into a constant interaction due to structural lacking.

Selecting color as a difference isn't identifying anything essential, a fact can be true but still draw one away from what is the essence of the matter.

If you read those links from Ilyenkov, you might get a grasp of the sort of distinction that is being raised.

Otherwise you will at best reach the point of Kant and still be arbitrary in your logic and selection of features as if concepts are applied externally to the empirical reality.

https://www.marxists.org/archive/ilyenkov/works/essays/essay3.htm

Having thus drawn the boundaries of logic (‘that logic should have been thus successful is an advantage which it owes entirely to its limitations, whereby it is justified in abstracting indeed, it is under obligation to do so from all objects of knowledge and their differences....’), Kant painstakingly investigated its fundamental possibilities. Its competence proved to be very narrow. By virtue of the formality mentioned, it of necessity left out of account the differences in the views that clashed in discussion, and remained absolutely neutral not only in, say, the dispute between Leibniz and Hume but also in a dispute between a wise man and a fool, so long as the fool ‘correctly’ set out whatever ideas came into his head from God knew where, and however absurd and foolish they were. Its rules were such that it must logically justify any absurdity so long as the latter was not self-contradictory. A self-consistent stupidity must pass freely through the filter of general logic.

Ricardo's labour theory of value was dismissed for its contradictory character, when in fact he was on the right path. Some contradictions are simply errors in ones reasoning, others are more a reflection of the essential quality of a problem.

It is when one identifies the essential fact, the concrete universal, that one resolved the contradiction. Like how Marx distinguishes labour power from labor, he in fact resolved a a contradiction in Ricardo's work.

Marx also resolved the epistemological dichtonomy between materialism and idealism in following Hegel's emphasis on activity as a substance.

http://critique-of-pure-interest.blogspot.com/2011/12/between-materialism-and-idealism-marx.html

For the point of his first Thesis on Feuerbach is exactly that the truth lies in the middle: between idealism and materialism, between humanism and postmodernism. That elusive middle is captured by Marx’s claim that the external object, on which humanity depends, is in turn dependent on the formative power of human activity. In other words: nature determines (causes, affects) man, who in turn determines (works upon) nature. Thus man is indirectly self-determining, mediated by nature. This reciprocal determination of man and nature is what Marx means by “praxis". In the first Thesis, therefore, Marx reproaches traditional materialism for not seeing this fundamental importance of praxis, since it (materialism) sees man one-sidedly as subjected to nature and thus it forgets man’s active intervention in nature

...